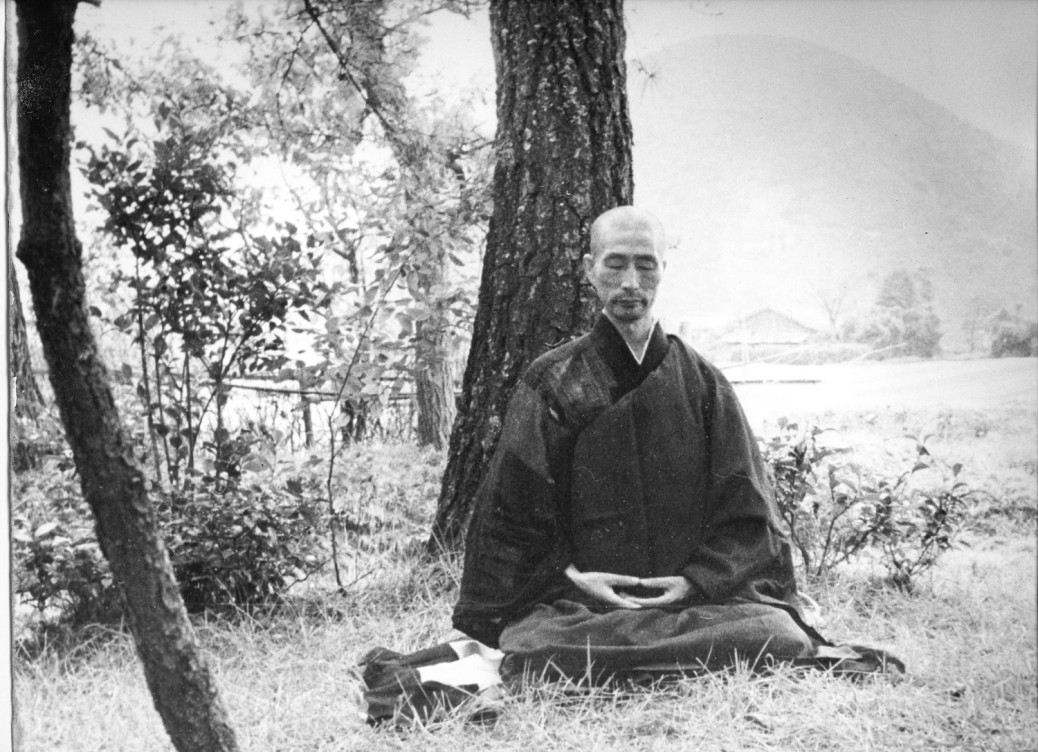

Once when Zen master Bankei was about to leave a temple in the capital where he taught from time to time, a certain gentleman came requesting that the master postpone his departure. A certain baron had a question and wanted to see the Zen master in person on the morrow to resolve it.

Bankei agreed and put off leaving.

The next day, however, the gentleman came again, this time with a message that the baron had some urgent business to take care of and could not come and see the master. The baron had asked the gentleman to relay his question to Bankei, then report the Zen maste’s answer back to him.

When he heard the gentleman out, Bankei said, “This matter of Zen is difficult to convey even by direct question and direct answer; it is all the more difficult to convey by messenger.”

The Zen master said nothing more. Speechless, the gentleman withdrew and departed.

Awakened To Buddha-Nature

Zen masters deal directly with seekers. They don’t need any messenger. As the question can be answered only when you are Awakened To Buddha-Nature.

Zen questioning is a simple and direct method that helps you uncover your own buddha-nature. It was developed in China from the sixth century onwards, in reaction to the scholastic tradition of the time, which relied heavily on the scriptures. The Zen school wanted to get back to the Buddha’s original message of practicing meditation and realizing awakening in this life. Zen questioning uses koans – past stories of awakening – as a starting point for meditative enquiry. There are seventeen hundred official Zen koans and new ones are created all the time.

‘What is this?’ is the question used most often in Korean Zen practice.

Let me share with you one koan so everyone of us will get an idea of Zen teaching.

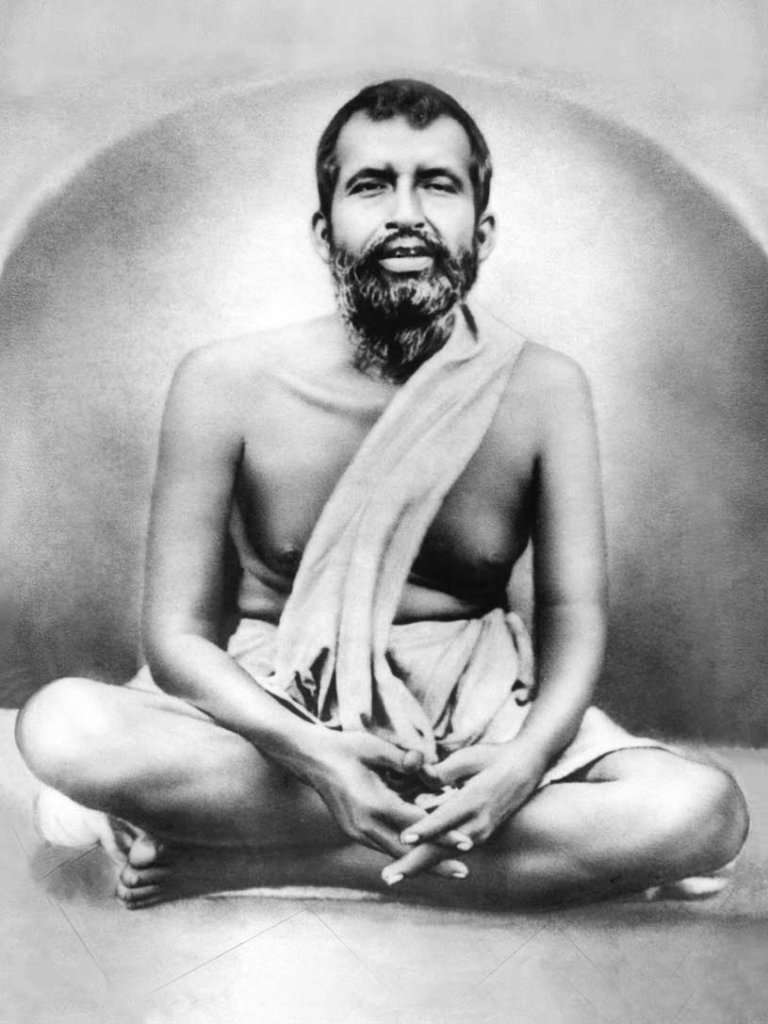

The young monk, Huai-jang, had walked many days to reach the patriarch. When he met him, the patriarch asked: ‘Where do you come from?’

‘From Mount Sung,’ replied Huai-jang.

The patriarch asked further: ‘What is this and how did it get here?’

Huai-jang remained speechless. He could not answer and remained to practice and ponder this question.

After eight years he had an insight and went to the master.

‘What is this?’ asked Hui-neng.

‘To say it is like something is not to the point. But still it can be cultivated,’ replied Huai-jang.

The whole story is the koan but its essential point is the question ‘What is this?’ The practice is very simple. Whether you are walking, standing, sitting or lying down, ask repeatedly ‘What is this?’ You are not looking for an intellectual answer so your question should not be an intellectual enquiry. In this moment, you are turning the spotlight onto yourself and your whole experience. You are not asking: ‘What is this thought?’ or ‘What is this sensation?’ If you need to put the question into a meaningful context, you are asking ‘What is it that is thinking?’ or ‘Before you think, what is this?’ You are not asking ‘What is the taste of the tea,’ but ‘What is it that tastes the tea?’ or ‘What is it before you even taste the tea?’

Master Kusan used to point out that what you question is not an object because it cannot be described in terms of size or color. It is not empty space because

empty space cannot ask a question. It is not a Buddha because it is not yet awakened to buddha-nature. It is not the master of the body, the source of consciousness or any other designation, because these are mere words and not the actual experience of what it is. So you are left with the questioning. You ask ‘What is this?’ because you do not know.

Concentration and enquiry are combined in one method in this technique. Concentration is developed as you come back again and again to the words of the question. ‘What is this?’ is the fixed point of the meditation; it brings you back again and again to the present moment. The question is alive but you are calm and focused when you ask it. In that moment of experience, you are aware of everything as you ask the question diligently and sincerely.

Learning from the story Direct Question: Awakened To Buddha-Nature

Experience Learning

Enquiry is vivid because the words are not repeated like a mantra. In themselves, the words do not have special resonance nor are they sacred. They function as a diving board to help you throw yourself into a pool of questioning. Do not put special emphasis on any specific word of the question. The most important part of the question ‘What is this?’ is the question mark.

Question unconditionally without expecting anything. Give yourself totally to the question. Zen questioning is like diving, which engages the whole body as you jump, not just the arms or legs. Then the whole body and mind are refreshed as you dive into the cool pool. Try to develop a sensation of questioning similar to the bewilderment you feel when you have lost something. You are going somewhere and you put your hand in your pocket to grab your car keys. They are not there. Before you try to rationalize and think of where else they might be, there is a moment when you are totally perplexed. This is very similar to the sensation you are trying to develop in Zen questioning.

Questioning makes you more open and flexible and creates space in your mind. It gives you energy because there is no place to mentally rest or grasp. It allows for less certainty, more possibilities and the kind of wonderment with which a young child discovers and marvels at the world. It means being immediate and responding in a creative way to the situation at hand, and not being lost in the future or the past. It is not trying to explain away or judge or analyze. It is just being with the moment, looking deeply, asking ‘What is this?’ and being open to experience as it is.

The Questioning Mind

There are different ways to meditate with Zen questioning. The easiest is to ask the question in combination with the breath. Breathe in and then, as you breathe out, ask ‘What is this?’ Master Kusan used to suggest asking the question as a circle. Start with

‘What is this?’ and as soon as one question is ended, start another ‘What is this?’

An alternative is just to ask the question once and remain for a while with the sensation of questioning. As soon as it fades away, bring back the feeling with another question and again stay with the pregnant sense of questioning till it dissipates. Young people have to be very careful not to ask the question in an intensely intellectual way. Ask from the belly or even from the toes. You need to bring energy down the body and not focus it in the head. If the question makes you feel speculative, confused or agitated, just come back to the breath, to a simple and calming practice.

You are not trying to force yourself to find an answer. You are giving yourself wholeheartedly to the questioning. The answer is in the questioning itself, in the tasting of the question. When you tell children who have never seen snow that it is white and cold, they might think of a piece of white paper in the fridge. If you show them the top of a mountain in the distance, they might imagine that snow tastes like coconut ice-cream. Only when they touch the snow, play with it and taste it do they really know what snow is. And with the question ‘What is this?’ The tasting is in the questioning itself.

The most important thing in Zen questioning is for the question to remain alive, for your whole body and mind to become a question. In Zen they say that you have to ask with the pores of your skin and the marrow of your bones.

As a Zen saying points out:

Great questioning, great awakening;

little questioning, little awakening;

no questioning, no awakening.

Tags: Awakened To Buddha-Nature Direction Koan Laughter Transcends Responses