The most striking quality common to all primitive art is its intense vitality. It is something made by a people with a direct and immediate response to life. – Henry Moore

Then Have A Cup Of Tea

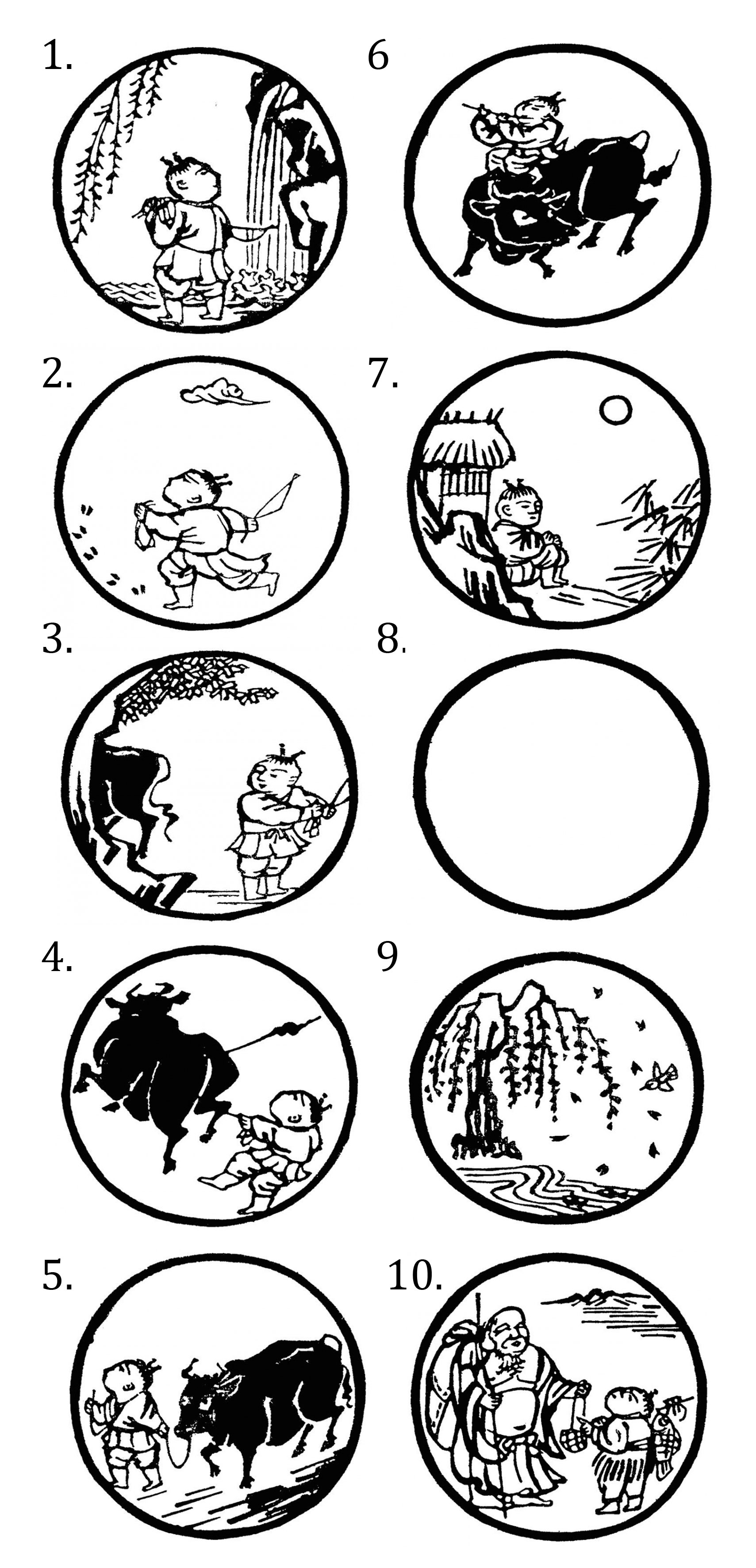

The first thing to be understood is that complex things can be understood, simple things cannot. A simple thing is alone. This Joshu story is very simple. It is so simple it escapes you: you try to grip it, you try to grab it — it escapes. It is so simple that your mind cannot work on it. Try to feel the story. I will not say try to understand because you cannot understand it — try to feel the story. Many things are hidden if you try to feel them; if you try to understand it nothing is there — the whole anecdote is absurd.

Joshu saw one monk and asked, “Have I seen you before?”

The man said, “No sir, there is no possibility. I have come for the first time, I am a stranger — you could not have seen me before.

Joshu said, “Okay, then have a cup of tea.” Then he asked another monk, “Have I seen you before?”

The monk said, “Yes sir, you must have seen me. I have always been here; I am not a stranger.”

The monk must have been a disciple of Joshu’s, and Joshu said, “Okay, then have a cup of tea.”

The manager of the monastery was puzzled: with two different persons responding in different ways, two different answers were needed. But Joshu responded in the same way — to the stranger and to the friend, to one who has come for the first time and to one who has been here always. To the unknown and to the known Joshu responded in the same way. He made no distinction, none at all. He didn’t say, “You are a stranger. Welcome! Have a cup of tea.” He didn’t say to the other, “You have always been here, so there is no need for a cup of tea.” Nor did he say, “You have always been here so there is no need to respond.”

Familiarity creates boredom; you never receive the familiar. You never look at your wife. She has been with you for many, many years and you have completely forgotten that she exists. What is the face of your wife? Have you looked at her recently? You may have completely forgotten her face. If you close your eyes and meditate and remember, you may remember the face you looked on for the first time. But your wife has been a flux, a river, constantly changing. The face has changed; now she has become old. The river has been flowing and flowing, new bends have been reached; the body has changed. Have you looked at her recently? Your wife is so familiar there is no need to look. We look at something which is unfamiliar; we look at something which strikes us as strange. They say familiarity breeds contempt: it breeds boredom.

I have heard one anecdote: two businessmen, very rich, were relaxing on Miami Beach. They were lying down, taking a sunbath. One said, “I can never understand what people see in Elizabeth Taylor, the actress. I don’t understand what people see, why they become so mad. What is there? You take her eyes away, you take her hair away, you take her lips away, you take her figure away, and what is left, what have you got?”

The other man grunted, became sad and replied, “My wife — that’s what’s left.”

That is what has become of your wife, of your husband — nothing is left. Because of familiarity, everything has disappeared. Your husband is a ghost; your wife is a ghost with no figure, with no lips, with no eyes — just an ugly phenomenon. This has not always been so. You fell in love with this woman once. That moment is there no longer; now you don’t look at her at all. Husbands and wives avoid looking at each other. I have stayed with many families and watched husbands and wives avoid looking at each other. They have created many games to avoid looking; they are always uneasy when they are left alone. A guest is always welcome; both can look at the guest and avoid each other.

Joshu seems to be absolutely different, behaving in the same way with a stranger and a friend. The monk said, “I have always been here sir, you know me well.”

And Joshu said, “Then have a cup of tea.” The manager couldn’t understand. Managers are always stupid; to manage, a stupid mind is needed. And a manager can never be deeply meditative. It is difficult: he has to be mathematical, calculating; he has to see the world and arrange things accordingly. The manager became disturbed. What is this? What is happening? This looks illogical. It’s okay to offer a cup of tea to a stranger but to this disciple who has always been here? So he asked, “Why do you respond in the same way to different persons, to different questions?”

Joshu called loudly, “Manager, are you here?”

The manager said, “Yes sir, of course I am here.”

And Joshu said, “Then have a cup of tea.” This asking loudly, “Manager, are you here?” is calling his presence, his awareness. Awareness is always new, it is always a stranger, the unknown. The body becomes familiar not the soul — never. You may know the body of your wife; you will never know the unknown hidden person. Never. That cannot be known, you cannot know it. It is a mystery; you cannot explain it. When Joshu called, “Manager, are you here?” suddenly the manager became aware. He forgot that he was a manager, he forgot that he was a body; he responded from his heart. He said, “Yes sir.”

This asking loudly was so sudden, it was just like a shock. And it was futile, that’s why he said, “Of course I am here. You need not ask me, the question is irrelevant.” Suddenly the past, the old, the mind, dropped. The manager was there no more — simply a consciousness was responding. Consciousness is always new, constantly new; it is always being born; it is never old. And Joshu said, “Then have a cup of tea.” The first thing to be felt is that for Joshu, everything is new, strange, mysterious. Whether it is the known or the unknown, the familiar or the unfamiliar, it makes no difference. If you come to this garden every day, by and by you will stop looking at the trees. You will think you have already looked at them, that you know them. By and by you will stop listening to the birds; they will be singing, but you will not listen. You will have become familiar; your eyes are closed, your ears are closed. If Joshu comes to this garden — and he may have been coming every day for many, many lives — he will hear the birds, he will look at the trees. Everything, every moment, is new for him.

This is what awareness means. For awareness everything is constantly new. Nothing is old, nothing can be old. Everything is being created every moment — it is a continuous flow of creativity. Awareness never carries memory as a burden.

Every new beginning comes from some other beginning’s end. – Seneca

Tags: FamiliarityYouth is not a time of life; it is a state of presence; it is not a matter of rosy cheeks, red lips and supple knees; it is a matter of the awareness, quality of the spontaneity, a vigor of the self; it is the freshness of the deep springs of life. – Dhwani Shah